Black Friday. These words have become synonymous with amazing deals, long lines, and cut-throat shopping, but in 1869, those words conjured up a different vision. Gold’s Black Friday, September 24, 1869, saw the collapse of the U.S. gold market, as unscrupulous financiers, and large federal debt converged together to create the perfect situation for an attempt to corner the gold market.

It’s 1869. The Civil War had recently ended, and the Reconstruction Era was underway, as Ulysses S. Grant, renowned war hero, became the 18th President of the United States. He inherited a deeply divided nation, with large federal debt. In his inaugural address in January 1869, Grant demonstrated his commitment to gold-backed currency by insisting on repaying the war bond debt from the Civil War with gold. Greenbacks (paper dollars), which had been introduced to fund the Union march to war in 1961, represented the first issue of a federal paper currency since the collapse of the Continental Currency of the late 18th century. These notes, which were originally intended to be temporary and to be recalled following the war, had more than $450 million worth in circulation. Due to hard times of 1867, particularly by western farmers, demands were made for an inflated currency through the creation of more greenbacks. A compromise was finally reached in 1869, whereby greenbacks to the amount of $356 million were left in circulation. Grant tried to improve the economy by reducing the supply of greenbacks, or paper dollars by using gold to buy dollars from citizens at a discount and replacing them with currency backed by gold. This effectively set the value of gold: when the government sold its supply, the price went down; when it didn’t, the price would go up.

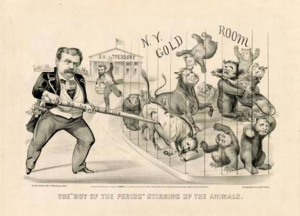

Enter Gould and Fisk. Jay Gould and Jim Fisk had a reputation for being two of Wall Street’s most ruthless financial masterminds. The two men, president and vice president of the Erie Railroad respectively, where known, among a slew of other misdeeds, for having issued fraudulent stocks, bribing politicians and judges, and maintaining a relationship with Tammany Hall’s William “Boss” Tweed. Beginning in early 1869, Gould, coupled with partner in crime, Fisk, began an ambitious campaign to conquer the gold market. Gould wagered that, because there was only around $20 million of gold in circulation at a given time, a speculator could potentially buy large portions of gold, and corner the market. From there, the price of gold could be driven up, and then sold for a hefty profit. Grant could simply order the Treasury to sell off large amounts of gold to drive prices back down, so for this ambitious gold scheme to work, Gould needed to manipulate the President of the United States.

An insider was needed. Abel Rathbone Corbin became the perfect partner-in-crime; a former Washington bureaucratic, and married to Grant’s sister, Virginia. In the spring of 1869, Corbin was befriended by Gould, and persuaded to help. $1.5 million in gold made its way into an account with Corbin’s name, and the conspiracy began. Corbin recruited Daniel Butterfield, who he helped install as the U.S sub-treasurer in New York. Butterfield was responsible for handling the government’s gold sales, and he agreed to give Gould, Fisk, and Corbin information of when the government was going to sell gold. Butterfield was given a $1.5 million stake in the scheme, and a $10,000 loan. The players were in place.

The deceit is on. Corbin began by playing up his family connections, often arranging meetings where Gould, Fisk and Grant would be present. The conspirators would use these occasions to talk about government money policy, with Corbin backing them in these discussions. The financiers argued against the government sale of gold, and tried to persuade Grant that high gold prices would benefit farmers. By raising the gold prices, greenbacks would be devalued, making U.S crops cheaper abroad, leading to boosted exports. President Grant remained cordial, but tight-lipped, around Gould and Fisk, but apparently, their plan worked. Grant confided in Corbin that he had changed his mind, and the treasury was going to be told not to sell gold for over the next month.

The buying begins. Gould, along with co-conspirators, had been secretly stockpiling gold since August. By September 16, they had nearly $10 million (2/3 of the total market) in gold. But when they became privy to the policy change, they began to acquire gold at an accelerated rate. Starting on September 20, hiding behind an army of brokers, they began to buy all the gold they could get their hands on. Just as planned, the gold price went higher, rising by 20%. At this point, Grant became suspicious of Corbin’s interest in gold, and asked his wife, Julia Grant, to write a letter to his sister, Virginia. She informed her that the president was “very much annoyed by your speculations. You must close them as quick as you can.” Corbin informed Gould of this new development, but Gould didn’t divulge the information to his partner, Fisk. On the evening of September 23, President Grant communicated with Secretary Boutwell, head of Treasury, and made the decision to sell $4 million in gold. Butterfield caught wind of the plan, and informed Gould of the new developments, but again, Gould didn’t tell Fisk. On Friday, September 24, at market’s open, Fisk was still buying gold. Gold opened at $145 but quickly spiked to $160, bringing the price of an ounce of gold to more than $30 above what it was when Grant took office.

The “Boy of the period” stirring up the animals, 1869. Print shows a caricature of financier Jay Gould, left, who attempts to corner the gold market, represented by bulls and bears in a cage. Credit: Library of Congress

Panic ensues. At about noon, on the fated “Black Friday”, word got out that the Treasury had sold $4 million in gold. Within minutes, the inflated gold prices plummeted from $160 to $133. Many investors had purchased gold on margin, and others had been locked into purchase contracts. When the price fell, other commodity prices destabilized, foreign trade was nearly halted, and investors faced financial ruin. The stock market fell 20%, and by some reports, 50 Wall St brokerages collapsed, and another 150 were insolvent. Gould, having been aware of the impending Treasury sale, was selling quicker than Fisk was buying before the collapse. Their holdings were sold, netting them around $15 million.

The aftermath. It was very chaotic after Black Friday, and the results were felt for years. To protect themselves, Gould paid off William “Boss” Tweed, along with some New York judges, delaying settlements of unfavorable trades. Multiple allegations of malfeasance and an official investigation by Congress proved fruitless. Fisk, who had bought gold contracts on behalf of other investors, simply reneged on the deals. Ultimately, they were able to keep the illicit earnings. Neither man ever spent a day in jail. But not everyone left unscathed. Corbin lost big on that day, and Butterfield was removed from his post. Ulysses S. Grant spent the rest of the term with the shadow of Black Friday hanging over him.

Black Friday. September 24, 1869, a historical day for gold prices, brought about by the conniving of ruthless and greedy men.

[1] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0014498375900133

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/1016.html

http://www.history.com/news/the-black-friday-gold-scandal-145-years-ago