LilliDay

LilliDayIt’s a human shortcoming to favor simple explanations for the business cycle. The notion that reliability and timeliness can be forged in one indicator endures, but recent history has hammered this approach, reminds a new commentary from Axios.

“Recession indicators don’t work like they used to,” the news site reports. “Many of them have been tripped, yet no big downturn has materialized. The quirks of the pandemic business cycle – driven by a rolling series of disruptions to supply and demand – are the likely culprit.”

Among the indicators that have failed to provide timely signals of an approaching recession: the yield curve, the Leading Economic Index, and temporary help employment, which Axios notes “was big tell” in the past but has stumbled recently.

It’s tempting to blame the after-effects of the pandemic for the false signals. To be fair, much has changed for the business cycle since covid upended the usual routine, and it would be naive to minimize this factor. But it’s also fair to observe that no one business-cycle indicator has ever been flawless. That’s always been true, and always will be. Forecasting, as the saying goes, is hard, especially about the future.

Fortunately, there are techniques to minimize the noise, maximize the signal and boost the timeliness and reliability of recession analytics. It starts with a basic premise that’s been documented for decades in empirical analytics: combining modeling analytics enhances results.

Regular readers of CapitalSpectator.com know that your editor is a big fan of ensemble methodologies for estimating real-time recession risk. As I wrote in 2016, “we should be wary of relying on market signals alone for estimating recession risk.”

Eight years later, the same principle applies, and for a good reason: it works. Or, to be more accurate, it fails less often than the usual suspects. Granted, it’s impossible to develop a genuinely flawless methodology. Indeed, there’s a crucial tradeoff that must be recognized in recession analytics: timeliness vs. reliability. The two are in conflict with one another. Although there’s no one perfect answer for calibrating this relationship in modeling, ignoring this hard fact by relying on one, even a handful of indicators, is asking for trouble.

In fact, one could argue that building a multi-factor recession model is more relevant and practical than ever. All the more reason that this core principle has long informed the methodology of weekly updates of The US Business Cycle Risk Report (now in its 10th year), a sister publication of CapitalSpectator.com. At a high level, the main focus is carefully curating a diversified set of indicators to estimate the current state of the economy. Using that foundation, a near-term forecast is updated weekly. The key principle: the estimates reflect a wide variety of indicators and models. The reasoning: it’s never clear which indicator or model will fail in real time–and, yes, something’s always failing. It’s the aviation equivalent of recognizing that if you’re flying across the Pacific, it’s well-advised not to rely on one engine.

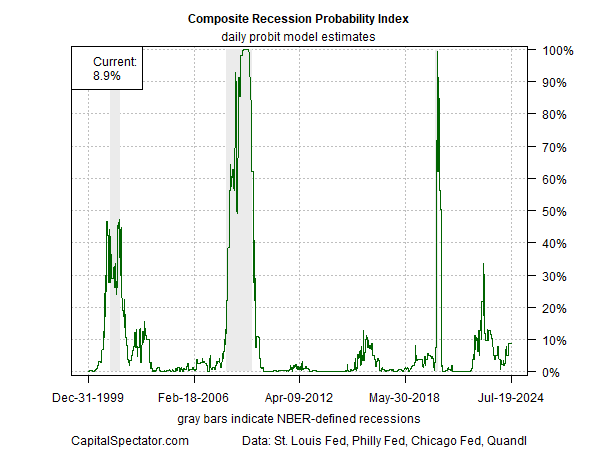

On that basis, the current state of the economy continues to favor expansion, based on the main indicator that aggregates a variety of signaling for The US Business Cycle Risk Report. In the current issue of the newsletter, the probability that an NBER-defined recession has started or is imminent is roughly 9%.

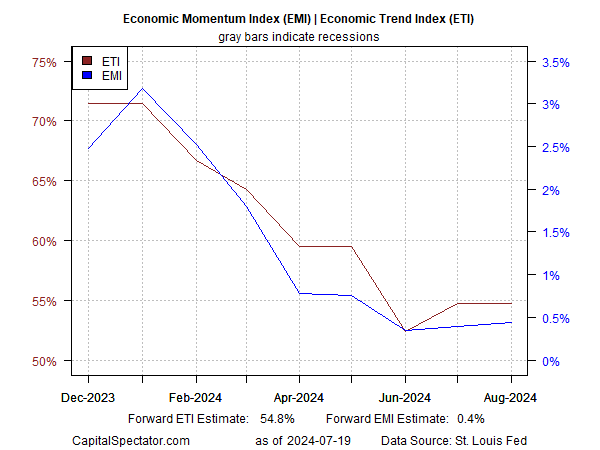

Using a multi-factor set of proprietary business-cycle indicators to forecast the near-term outlook suggests that economic activity is stabilizing through August, albeit at a slow/sluggish pace. Note: the tipping points that separate expansion from recession for the indexes in the chart below are 50% (ETI) and 0% (EMI).

Why limit the forward estimates to a month or two? Because looking out much further is guessing. It’s deeply flawed/naive to assume that it’s possible to model how the complexity of the US economy will involve much beyond the very near future. Indeed, the only thing more deeply flawed than relying on one indicator in recession analysis is forecasting six-month, a year, or longer.

Shared by Golden State Mint on GoldenStateMint.com