The price of gold is setting a string of all-time records, buoyed by strong physical demand. The rush to buy the precious metal is intensifying as investors and institutions seek to secure their assets in the face of economic uncertainty.

Stress signals are multiplying on the market, with delivery times lengthening, inventories under pressure and bullion premiums soaring. This upward movement reflects a growing crisis of confidence in paper gold and official gold reserves, as market players increasingly demand physical deliveries.

This week, StoneX’s CEO sprang a surprise by declaring on Sky News Arabia that over 2,000 tons of gold had been transferred to the USA in the space of a few weeks.

Philip Smith warned of a persistent price discrepancy between gold futures in New York (COMEX) and the physical OTC market in London. This divergence, oscillating between $25 and $30 an ounce, impacts market efficiency and reflects a climate of uncertainty exacerbated by the Trump administration’s trade policies.

Since November, the threat of tariffs (up to 25%) has disrupted gold flows and pricing. In response, over 2,000 tons of gold have been transferred to the United States in recent weeks, a massive movement fueled by investors’ desire to protect themselves in the face of regulatory ambiguity.

Two thousand tons of gold… a staggering figure. It illustrates a veritable rush for physical gold, revealing a clear urgency to move all available metal to the United States. The unprecedented scale of this movement reflects growing concern about tensions on the gold market and the future availability of the metal.

This massive transfer reflects a loss of confidence in the storage of gold abroad, particularly in London, which has always occupied a central position in the precious metals market. The idea that a country as powerful as the USA considers it essential to secure such a large volume of gold on its territory fuels speculation about possible future shortages or a reconfiguration of the international monetary system.

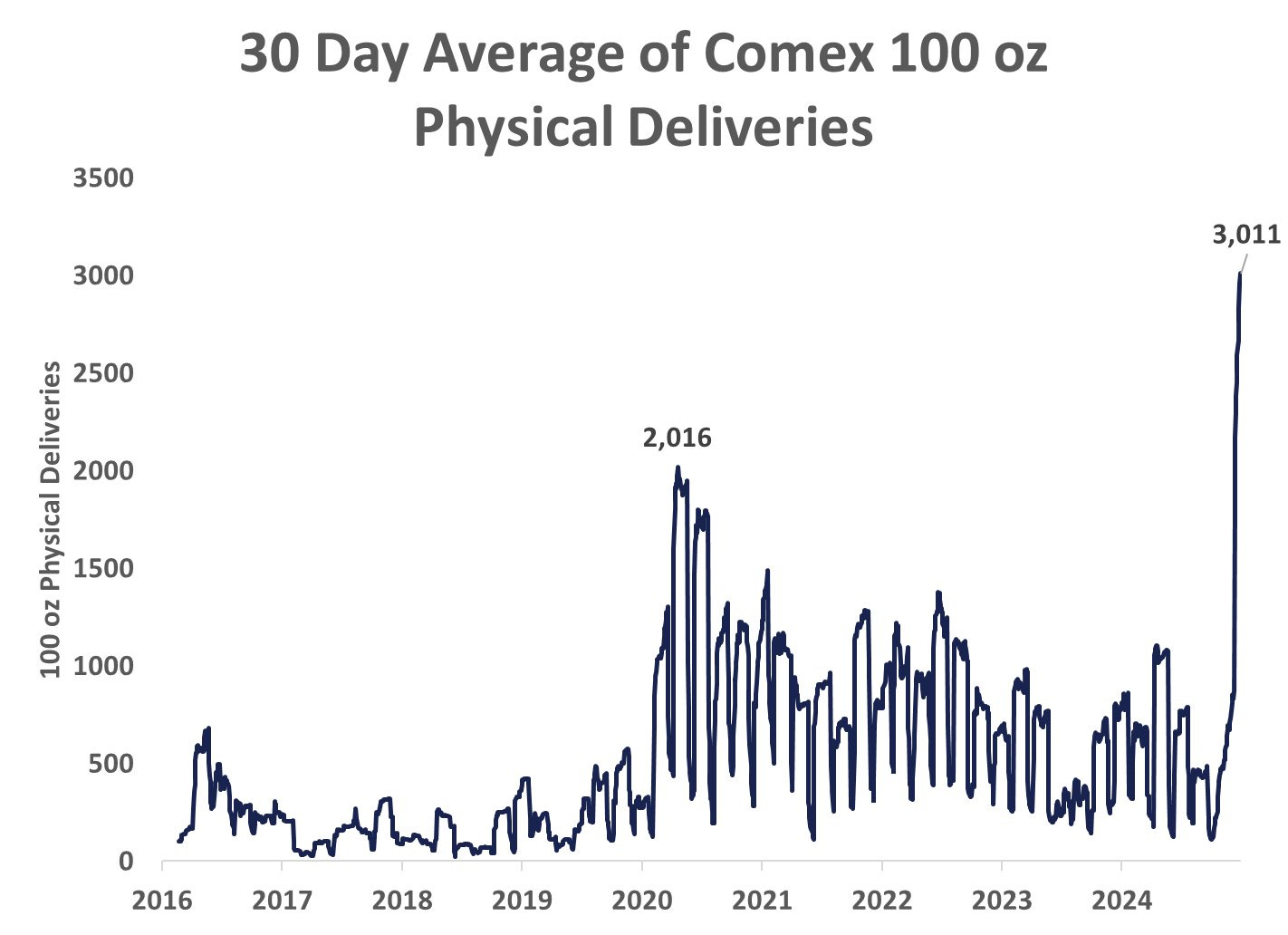

At the same time, gold deliveries on the COMEX are reaching record levels, a clear indicator of the explosion in demand for physical gold. This phenomenon could create a snowball effect, prompting other major institutions and central banks to step up their delivery demands, putting further pressure on the system as a whole.

The explosion in gold deliveries on the COMEX is upsetting the traditional balance between the LBMA (London, physical OTC market) and COMEX (New York, futures market) markets.

Historically, these two markets functioned in symbiosis: the LBMA ensured the liquidity and availability of physical gold, while the COMEX served primarily as a platform for paper transactions and risk management via futures contracts. The majority of investors and institutions never took physical delivery on COMEX, preferring to roll over their positions or settle in cash.

But today, this dynamic is changing radically. The massive increase in delivery requests on the COMEX shows that more and more players are demanding physical metal, calling into question the viability of the paper market. If this trend continues, the COMEX could be forced to adjust its operations in line with the physical market, which could create considerable pressure on gold stocks and further accentuate the divergence between the two markets.

Such a break could mark a historic turning point, when paper gold would no longer be sufficient to satisfy real demand, and only physical possession of the metal would have any real value.

Let’s take a closer look at how this arbitrage works:

Arbitrage between the LBMA (London – OTC spot market) and the COMEX (New York – futures market) is based on a stable relationship between gold prices on these two markets. Banks and traders exploit these price differentials to generate profits by buying on one market and selling on the other.

The banks use classic arbitrage between the COMEX (New York – futures contracts) and the London spot market. They sell futures on the COMEX while simultaneously buying physical gold in London, generating a gain.

In a bull market, these banks roll over their short positions on the COMEX while lending the gold they buy in London on the OTC market to lock in an extra profit. When prices fall, they reverse the strategy, selling the gold in London and buying back their short positions on the COMEX to maximize their gains.

However, when there is strong demand for physical gold, this balance is completely upset, rendering arbitrage ineffective and even catastrophic for those involved.

Normally, the price of gold on the COMEX and the LBMA are relatively synchronized. If a slight discrepancy appears, traders can take advantage of it by buying physical gold in London when it’s cheaper, and selling futures on the COMEX, or vice versa. This arbitrage mechanism generally presents little risk, as long as banks can easily buy and sell physical gold to adjust their positions.

But when physical demand explodes, buyers flock to the London market for bars, creating a supply shock that reduces the availability of gold and drives up its price relative to COMEX futures. This leads to a major divergence between the LBMA spot price and COMEX futures, making arbitrage impossible. What’s more, the scarcity of available bars prevents traders from balancing the market, and those who are short on COMEX find themselves in a critical situation, as they are counting on a stable supply of physical gold to honor their commitments.

In this context, banks that have sold futures contracts on the COMEX generally have to buy physical gold in London to hedge their position. However, when physical gold becomes unavailable or too expensive, they find themselves unable to convert their short positions on the COMEX into a physical position on the LBMA. Their only option is to buy back their short positions in a hurry, further fueling the rise in prices and generating massive losses.

This imbalance rapidly reinforces itself in a vicious circle. Massive demand for physical gold pushes up spot prices, arbitrage becomes impossible as there is no gold left in London to balance flows, and COMEX short traders find themselves trapped. Forced to buy back their positions, they drive futures prices even higher. This panic spreads to other market participants, creating an uncontrollable acceleration in price rises.

Strong physical demand therefore acts like a hurricane on LBMA-COMEX arbitrage. It suppresses the supply of physical gold, causes the spread between the spot and futures markets to explode, and forces short sellers to buy back at a loss, turning a stable arbitrage strategy into a death trap for banks. This phenomenon can lead to total market distortion, with colossal losses for the financial institutions that depend on it.

The LBMA’s current rush to buy physical gold highlights a major risk linked to the management of banks’ short positions in the gold market. These institutions could be faced with a physical liquidity crisis, forcing them to draw on the reserves of gold-backed ETFs to cover their obligations.

When a bank sells a gold futures contract short (short COMEX), it is supposed to hold physical gold in reserve to ensure delivery in case of need. As long as it actually owns this gold, it can honor its commitments without difficulty. However, banks often use this physical stock for other operations, notably by lending it via the OTC (Over-the-Counter) market in the form of gold leasing.

This dual use creates a critical problem. On the one hand, the bank has sold gold on the COMEX, on the assumption that it will be able to supply physical gold if required. On the other hand, this gold has been lent to other market players, who must return it at a later date. If the bank is called upon to deliver its gold, and the borrower is unable to return it immediately, it finds itself trapped. If several banks simultaneously find themselves in this situation, it could lead to a shortage of physical gold, triggering a short squeeze in which they would be forced to buy back futures contracts at dizzying prices to meet their commitments.

Faced with this impasse, banks might be tempted to source gold elsewhere, notably from gold ETFs such as the SPDR Gold Trust (GLD). These funds are supposed to hold physical gold equivalent to investors’ shares. However, some banks, benefiting from privileged access to these reserves, may withdraw physical gold from ETFs while leaving an IOU, thus using these reserves as a temporary back-up solution.

This practice represents a major risk for ETF investors. They think they are holding physical gold, but in reality, a portion of this gold may be used by banks to hedge their own positions. If a large number of investors request physical delivery of their gold, but it has already been mobilized for other purposes, this could lead to a collapse in confidence in ETFs and trigger a huge crisis in the gold market.

The current crisis highlights the potential fragility of the paper gold market. Banks could be forced to dip into ETFs to avoid default on delivery, triggering a massive short squeeze, a price surge and a questioning of ETFs’ role as a reliable reserve of physical gold.

Are we witnessing the end of paper gold? Currently, 100 ounces of paper gold are traded for every ounce of physical gold available on the market. If paper gold investors lose confidence in their counterparties against a backdrop of physical metal shortages, we’ll be witnessing a historic event in the gold market.

In such a scenario, institutions issuing paper gold would find themselves selling short an asset they could no longer obtain. The recent transfer of 2,000 tons of gold to the USA in the space of a few weeks sends a warning signal to all market players: issuers of paper gold certificates, gold account providers, managers of gold-backed ETFs, as well as all institutions that have allocated gold without any real physical hedge. Having sold an asset without physically owning it suddenly becomes a very high-risk activity for these institutions, as shortages of physical gold intensify. What was once common practice in a fluid market is now turning into a dangerous gamble, where failure to deliver is likely to trigger a major crisis of confidence and a historic short squeeze.

Unlike a short squeeze on a financial instrument, which can be easily circumvented by simply issuing more securities or electronic money, a short squeeze on physical gold is an entirely different matter. Here, it’s not enough to create new units with a single click: you have to buy and deliver real metal, the availability of which is getting scarcer by the day.

In a context of growing shortages, institutions trapped in a short squeeze on physical gold will have to fight to secure stocks that are increasingly difficult to obtain. This situation differs radically from a classic short squeeze on a financial asset, where supply can be artificially increased. When it comes to precious metals, the only solution is to acquire physical metal at any price, which could lead to a spectacular surge in prices.

This threat is already being taken very seriously by many investors. The rush to buy physical gold is causing supply shortages on the world market, heightening tensions and revealing the fragility of the current system.

In Japan, the Ishifuku platform is out of stock on silver bars, a clear sign that demand from retail investors is also shifting towards physical silver. This shortage is indicative of a wider phenomenon, where growing interest in precious metals is no longer confined to gold, but now extends to silver, exerting increased pressure on global supply.

In Singapore, Metalor Singapore has introduced a surcharge per ounce in addition to the standard premium on physical gold. This decision reflects growing tensions on the physical market and rising supply costs, highlighting an imbalance between supply and demand in the country.

Analyst Samsun Lin also reports that China is also short of bars according to local media: “Many Chinese banks have run out of gold bars as the demand has been strong. Those unsatisfied demand need to make arrangement with the bank and wait for a few weeks”

Argor-Heraeus is one of the world’s leading refiners of precious metals, specializing in the refining and manufacture of gold, silver, platinum and palladium bars. Based in Switzerland, the company plays a key role in supplying central banks, financial institutions, jewelers and investors with precious metals.

Argor-Heraeus will apply a “temporary surcharge” on gold and silver minted from February 20. The surcharge amounts to $3.50/oz for struck gold and $3/oz for silver, a massive 9.23% increase on the price of struck silver!

This surcharge applies at wholesale level, in addition to the usual premiums and minting costs.

This confirms that the spot price set by the LBMA no longer truly reflects the price of physical metal.

On the other hand, according to an article in the Financial Times of January 29, 2025, the delivery time for physical gold on the LBMA market has lengthened considerably.

The delay for withdrawing bars from the Bank of England (BoE) is now between four and eight weeks, whereas it used to be much shorter. This delay is probably due not only to the strong demand for repatriation from the USA, which is putting considerable pressure on stocks, but also to the fear that other holders of gold at the LBMA will in turn take similar steps.

These institutions legitimately wonder: if the United States proceeds with such a massive repatriation, is it still safe to keep one’s gold in London in LBMA vaults that are not audited?

It is in this context that President Donald Trump recently expressed doubts about the presence of US gold reserves at Fort Knox. During a flight aboard Air Force One, Trump declared his intention to verify whether gold is indeed present in the Fort Knox depository, claiming that if it isn’t, “we’re going to be very upset”.

This concern follows tweets from Elon Musk, in which he questioned the existence of US gold reserves. In response, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent assured that annual audits are carried out and that “all gold is present and accounted for”.

Meanwhile, Senator Rand Paul supports the idea of an official audit of Fort Knox, pointing out that the last full inspection dates back to 1974.

Ron Paul had already voiced his doubts about the actual presence of gold reserves at Fort Knox, reigniting a debate that has never been fully settled.

Today, Donald Trump’s initiative to audit these reserves risks adding further fuel to the fire of an already tense gold market. Should the gold at Fort Knox prove no longer to be fully available, the consequences for the stability of the US monetary system would be potentially devastating.

But beyond the simple question of whether gold is actually present, the real issue at stake in this audit lies in the inspection method that will be employed. Whatever the final results, it’s the transparency of the process that could raise the biggest questions. Have the bars been re-hypothecated? How many different beneficiaries claim ownership of the same gold bars?

If a rigorous audit of Fort Knox is carried out, it could pave the way for similar demands concerning other global gold reserves, notably those of the LBMA in London. How can we justify a lack of transparency on British stocks if the US undertakes an in-depth audit of its own reserves?

Trump’s initiative could therefore exacerbate the crisis of confidence surrounding paper gold. Against a backdrop of exploding demand for physical metal and growing doubts about the real convertibility of paper gold, this audit could be the trigger for a much wider movement of questioning, affecting the entire global precious metals market.